LAMB OF GOD

"The next day he saw Jesus coming to him and said, “Behold, the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!" ~ John 1.29

John, the cousin of Jesus who was preaching in the Judean Wilderness and baptizing in the Jordan River, saw Jesus approaching and made the most monumentous proclamation, “Behold, the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!”

This imagery, of a sin-carrying lamb, comes from the Exodus narrative where God commanded that the Hebrews take the blood of a one year old, male, unblemished lamb and paint it over the door posts of their homes. In so doing, the angel of death that was bringing judgment upon the Egyptians would “pass over” the Hebrew homes. This was the single most defining moment for the people of God whereby he delivered the people and started them on their journey to the Promised Land of Canaan. Every year after that, they were to celebrate the Passover and remember God’s great love for His people.

Here, John proclaims Jesus to be that lamb who brings rescue, not from Pharaoh of Egypt, but from sin. Jesus would ultimately lay down His life and willingly allow Himself to be sacrificed on our behalf and become our Passover Lamb. For all those who repent of their sin and place their faith in Jesus’ great sacrifice, God’s judgement will passover them when we stand before God at the Day of Judgement.

Prayer

Jesus, You are our perfect Lamb. Your willingness to lay down Your life for me is shaking. It’s unsettling. The love You have for me and for all Your creation, despite our faithlessness, despite our faults, despite our failures . . . it’s overwhelming. Thank you for loving me. Thank you for being my Lamb. Amen.

Agnus Dei ("Lamb of God") (1635-1640)

by Francisco de Zurbarán

(oil on canvas) (Museo del Prado)

Painted during the heights of the Spanish Catholic Reformation, Francisco de Zurbarán’s Agnus Dei is shocking in its simplicity of a lone Christian icon. The religious art of the Baroque period is frequently characterized by the dramatic works of Bernini, Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Rubens. Zurbarán, however, abandons drama for subtle poignancy.

Set against a black backdrop and laying upon a gray table, a live merino lamb is tied and bound in a sacrificial position; its legs are thrust into the foreground and its eyes avert our gaze. There is no other iconography only the heartbreaking sense that the melancholy lamb is resigned to its sad fate. While technically there is no iconography to suggest the allegory of Christ as the ‘Lamb of God’, the image was widespread throughout Christian imagery, especially in (predominantly) Catholic Spain.

Between 1631-40 he painted five versions of Agnus Dei for private patrons, with slight iconographic variants. Yet, it is the unadorned version that is considered the finest of the five. Its poignancy highlighted through Zurbarán’s ability to “concentrate the viewer’s attention on a lamb that seems to meekly accept its fatal destiny.” There is nothing to detract the viewer from the lamb’s sacrifice. No halo, no lilies. Only life–a life that will be given to pardon the sins of the world.

Agnus Dei is often treated as a still-life, a genre of painting frequently associated with food or perishables acting as a memento mori (an artistic trope about the inevitability of death). The lamb is indeed edible and its life coming to an end. Unlike most still-lifes, however, the process of death and/or decay is not shown for this is the food of life. The symbolism is two-fold. The unblemished sacrifice refers to the lamb of Passover, whose blood saved the Jews in Egypt and Christ, the Lamb of God, whose blood redeemed the sins all mankind. Zurbarán utilizes his artistic skill in rendering the texture of the lamb’s wool with a technical subtlety that further underscores this is a lamb without blemish. This indeed is the Agnus Dei who is acting as the pardon for our sins. It is also his body we are symbolically consuming during the Lord’s Supper.

Zurbarán forces the viewer to confront the paradoxical nature of Christ Biblically and as seen art historically. He is both the Good Shepherd and the lamb, divine and humble, the triumphant and the slain. As a relatively new religion, early Christian imagery favored more Johannine depictions of the Agnus Dei. Their god could not be shown as meek and humble, but rather as a glorious deity who conquered death.

By the 13th century, Franciscan theology created a shift in Christian imagery. Gone was the triumphant Lamb of Revelation, now replaced by a meek animal, humbly offering itself to humanity. This is the Lamb of God we encounter in Zurbarán’s poignant masterpiece. Agnus Dei enables us to “recognize in this wooly lamb, bound and patiently waiting on a slab for the butcher’s knife, the Saviour on the altar, the Son of Man suffering in atonement for our sins.” And it is this recognition of Christ’s complete and sorrowful surrender to death so that we shall live that makes Zurbarán’s Agnus Dei one of the most moving of all images in Christianity. (From blog The Artist’s Job: t.ly/6QvmH)

Agnus Dei (1635-1640) by Francisco de Zurbarán, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado. Compare Zurbarán's portrayal of Christ as Agnus Dei with those below which portray Jesus as the Cosmic Lamb (eternal ruler) and the Victorious Lamb on His throne in Revelation.

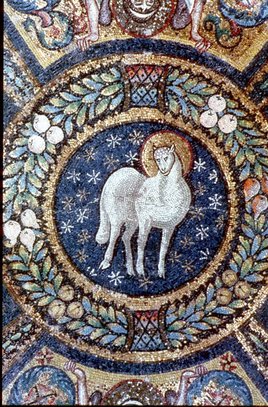

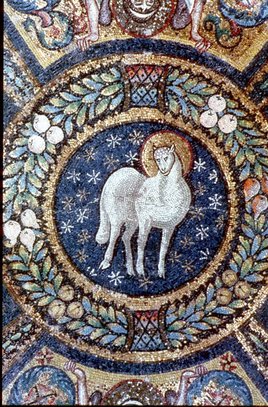

"Cosmic Lamb," dome of San Vitale, 6th Century, Ravenna, Italy.

"Lamb of God," early 7th Century, Rome. Referencing Lamb of Revelation.

Agnus Dei (1635-1640) by Francisco de Zurbarán, oil on canvas, Museo del Prado. Compare Zurbarán's portrayal of Christ as Agnus Dei with those below which portray Jesus as the Cosmic Lamb (eternal ruler) and the Victorious Lamb on His throne in Revelation.

"Cosmic Lamb," dome of San Vitale, 6th Century, Ravenna, Italy.

"Lamb of God," early 7th Century, Rome. Referencing Lamb of Revelation.

Painted during the heights of the Spanish Catholic Reformation, Francisco de Zurbarán’s Agnus Dei is shocking in its simplicity of a lone Christian icon. The religious art of the Baroque period is frequently characterized by the dramatic works of Bernini, Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Rubens. Zurbarán, however, abandons drama for subtle poignancy.

Set against a black backdrop and laying upon a gray table, a live merino lamb is tied and bound in a sacrificial position; its legs are thrust into the foreground and its eyes avert our gaze. There is no other iconography only the heartbreaking sense that the melancholy lamb is resigned to its sad fate. While technically there is no iconography to suggest the allegory of Christ as the ‘Lamb of God’, the image was widespread throughout Christian imagery, especially in (predominantly) Catholic Spain.

Between 1631-40 he painted five versions of Agnus Dei for private patrons, with slight iconographic variants. Yet, it is the unadorned version that is considered the finest of the five. Its poignancy highlighted through Zurbarán’s ability to “concentrate the viewer’s attention on a lamb that seems to meekly accept its fatal destiny.” There is nothing to detract the viewer from the lamb’s sacrifice. No halo, no lilies. Only life–a life that will be given to pardon the sins of the world.

Agnus Dei is often treated as a still-life, a genre of painting frequently associated with food or perishables acting as a memento mori (an artistic trope about the inevitability of death). The lamb is indeed edible and its life coming to an end. Unlike most still-lifes, however, the process of death and/or decay is not shown for this is the food of life. The symbolism is two-fold. The unblemished sacrifice refers to the lamb of Passover, whose blood saved the Jews in Egypt and Christ, the Lamb of God, whose blood redeemed the sins all mankind. Zurbarán utilizes his artistic skill in rendering the texture of the lamb’s wool with a technical subtlety that further underscores this is a lamb without blemish. This indeed is the Agnus Dei who is acting as the pardon for our sins. It is also his body we are symbolically consuming during the Lord’s Supper.

Zurbarán forces the viewer to confront the paradoxical nature of Christ Biblically and as seen art historically. He is both the Good Shepherd and the lamb, divine and humble, the triumphant and the slain. As a relatively new religion, early Christian imagery favored more Johannine depictions of the Agnus Dei. Their god could not be shown as meek and humble, but rather as a glorious deity who conquered death.

By the 13th century, Franciscan theology created a shift in Christian imagery. Gone was the triumphant Lamb of Revelation, now replaced by a meek animal, humbly offering itself to humanity. This is the Lamb of God we encounter in Zurbarán’s poignant masterpiece. Agnus Dei enables us to “recognize in this wooly lamb, bound and patiently waiting on a slab for the butcher’s knife, the Saviour on the altar, the Son of Man suffering in atonement for our sins.” And it is this recognition of Christ’s complete and sorrowful surrender to death so that we shall live that makes Zurbarán’s Agnus Dei one of the most moving of all images in Christianity. (From blog The Artist’s Job: t.ly/6QvmH)

Playlist Daily Highlight

Take the time to listen . . . really listen to the words of this song. Reflect on them. Let God’s spirit speak to you in this moment.